Background

In Myanmar, the future of food is soy. For Myanmar to achieve food security, it must strategically develop soya bean agriculture with improved inputs, and for Myanmar to become dairy independent, it must intentionally develop its soy dairy industry with new technology and infrastructure. To find sustainable solutions to protein malnutrition, it must judiciously seize the current opportunity to develop its distribution of soy products and encourage market expansion of value added products.

Soy is a super food that has been cultivated since the dawn of civilisation. Indeed, it is indicative of a civilised society. Soy food products are consumed all around the world and, from culture to culture, it is contextualised to create indigenous recipes, products and flavours. As such, it is a global and ubiquitous food second only to rice in terms of its universality, and first in terms of imaginative uses and versatility. Soy can be made into everything from automobile parts to nutritious dairy products, from wholesome snacks and health foods to meat alternatives for vegetarians. It is used to fuel cars and to both treat and prevent malnutrition related diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes and certain cancers. No other food on earth can claim such efficacy to human needs with the added benefit of being ethical and environmentally beneficial. When land once used to sustain cows is converted to soy cultivation, protein yields increase nearly tenfold. Moreover, food, such as beef, which once contributed more greenhouse causing emissions than automobiles, is replaced with food whose cultivation is actually removes carbon and requires nearly ten times less water, as well as other inputs.

History of Soy in Myanmar

Although the scope of our current research did not extend to the origin of soya bean agriculture and consumption in Myanmar, it is probable that soya bean has been cultivated in Myanmar for nearly as long as it has been in China, thus making soya a truly native crop to Myanmar. It is not unrealistic to assume that the food of the original settlers to Myanmar (who originated from the Yellow River and Mongolia) including the Karens, the Shans, the Kachins and the Pa’o people, was similar to that of the Chinese people who had been cultivating soya beans since as early as 2000BC. Soy is a staple in the diet of Shans and Pa’o and can be found in just about every Shan dish. New value added soy products are constantly appearing on the grocery shelves and research is being conducted into other uses for soy in Myanmar.

Current Market Conditions

In spite of all of soy’s potential for the Myanmar economy, environment and nutrition, the soy industry is struggling in Myanmar. In fact, the entire supply chain is embattled by low yields, global and regional market forces, low investment, foreign competition, substandard inputs and farming methodologies, lack of education, governmental indifference, disinformation and a lack of consumer awareness, among other things. If any interventions exist at all from NGOs or foreign investors, they are unfortunately inadequate, incidental and/or haphazard, despite the many needs and opportunities in this sector.

Indeed, nutritional and agricultural interventions that do occur on the part of NGOs and humanitarian organisations are generally focused in the area of carbohydrates production and consumption, but the issue of malnutrition in Myanmar is related more to a lack of protein than a lack of carbohydrates; rice and fruits and vegetables are in large supply.

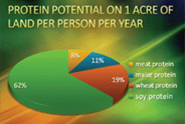

Moreover, programmes that focus on protein nutrition are usually focused on livestock and fish. To provide the amount of protein needed by the majority of Myanmar’s population of 60 million, simply increasing the meat supply will prove to be unsustainable. The input to output ratio are poor. Most of what a cow or pig consumes is to sustain itself and livestock require land that could be used to cultivate soy (refer to pie chart) and they produce waste that can contaminate the water supply.

Also, many of Myanmar’s Buddhists are vegetarians, at least for the period of Lent from April to September. Soy is the best vegetable source of protein (and better than most meats) for providing all the essential amino acids required for human health (refer to chart).

My experience in the Myanmar soy industry over the past several years has also revealed that there is great cause for optimism for the future of the soy industry and that Myanmar might become the ASEAN Brazil of soy production. The latest statistics show that 316,000 hectares are being used to cultivate soya bean in Myanmar, up from about 114,000 hectares in 2000 to 2001. This is phenomenal growth with minimal investment and incentives. Current yields are at about 16 bushels per acre and harvest losses are as high as 45 percent due to a lack of technology and other inputs, but with an intentional investment strategy, better inputs, training and other incentives, Myanmar could rapidly transform itself from a net importer of value added soy foods to a net exporter, not only of high quality raw soya bean, but also a diversity of innovative value added products, as well as a bustling domestic consumer of all things soy. The Myanmar ministry of agriculture is showing signs of a growing interest in developing its soy cultivation and there was great support from our contacts for this research.

Moreover, growers are showing tremendous resilience to market forces and deep desire to improve their yields through improved inputs. Growers associations and middlemen are tenacious in their desire to improve their ability to compete with Thai and Chinese growers and to develop new markets and uses for soy. Entrepreneurs across the country are researching and innovating and trying out new products (such as the made in Myanmar Vitagoat soy milk processing machine) and markets for domestic use. Our assertion is that, if even a small portion of the investment that is put into rice were put into the soy industry, we could create an agricultural and market revolution that will positively and significantly impact GDP and create food security, sustainability, livelihoods and environmental benefits.

Major Stakeholders

Over the past several years, I have interviewed people from the ministry of agriculture, educators at the University of Agriculture, food processing engineers, growers associations in four states and divisions (including Shan and Irrawaddy), growers, middlemen, merchants, NGOs and consumers. One thing we discovered that was clear and univocal was that Myanmar must strengthen its soy industry through investment and technological input, as well as through education and marketing. Every single stakeholder along the value chain and in the academic forum believed that it can be done and that it can be exceedingly successful and beneficial to the nation as a whole.